Electrostatic induction

| Articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

Electrostatic induction, also known as "electrostatic influence" or simply "influence" in Europe and Latin America, is a redistribution of electric charge in an object that is caused by the influence of nearby charges.[1] In the presence of a charged body, an insulated conductor develops a positive charge on one end and a negative charge on the other end.[1] Induction was discovered by British scientist John Canton in 1753 and Swedish professor Johan Carl Wilcke in 1762.[2] Electrostatic generators, such as the Wimshurst machine, the Van de Graaff generator and the electrophorus, use this principle. See also Stephen Gray in this context. Due to induction, the electrostatic potential (voltage) is constant at any point throughout a conductor.[3] Electrostatic induction is also responsible for the attraction of light nonconductive objects, such as balloons, paper or styrofoam scraps, to static electric charges. Electrostatic induction laws apply in dynamic situations as far as the quasistatic approximation is valid.

Explanation

[edit]A normal uncharged piece of matter has equal numbers of positive and negative electric charges in each part of it, located close together, so no part of it has a net electric charge.[4]: p.711–712 The positive charges are the atoms' nuclei which are bound into the structure of matter and are not free to move. The negative charges are the atoms' electrons. In electrically conductive objects such as metals, some of the electrons are able to move freely about in the object.

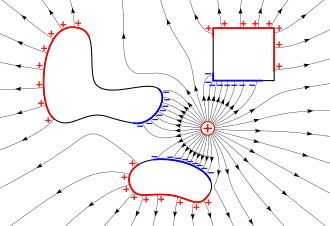

When a charged object is brought near an uncharged, electrically conducting object, such as a piece of metal, the force of the nearby charge due to Coulomb's law causes a separation of these internal charges.[4]: p.712 For example, if a positive charge is brought near the object (see picture of cylindrical electrode near electrostatic machine), the electrons in the metal will be attracted toward it and move to the side of the object facing it. When the electrons move out of an area, they leave an unbalanced positive charge due to the nuclei. This results in a region of negative charge on the object nearest to the external charge, and a region of positive charge on the part away from it. These are called induced charges. If the external charge is negative, the polarity of the charged regions will be reversed.

Since this process is just a redistribution of the charges that were already in the object, it doesn't change the total charge on the object; it still has no net charge. This induction effect is reversible; if the nearby charge is removed, the attraction between the positive and negative internal charges causes them to intermingle again.

Charging an object by induction

[edit]

However, the induction effect can also be used to put a net charge on an object.[4]: p.711–713 If, while it is close to the positive charge, the above object is momentarily connected through a conductive path to electrical ground, which is a large reservoir of both positive and negative charges, some of the negative charges in the ground will flow into the object, under the attraction of the nearby positive charge. When the contact with ground is broken, the object is left with a net negative charge.

This method can be demonstrated using a gold-leaf electroscope, which is an instrument for detecting electric charge. The electroscope is first discharged, and a charged object is then brought close to the instrument's top terminal. Induction causes a separation of the charges inside the electroscope's metal rod, so that the top terminal gains a net charge of opposite polarity to that of the object, while the gold leaves gain a charge of the same polarity. Since both leaves have the same charge, they repel each other and spread apart. The electroscope has not acquired a net charge: the charge within it has merely been redistributed, so if the charged object were to be moved away from the electroscope the leaves will come together again.

But if an electrical contact is now briefly made between the electroscope terminal and ground, for example by touching the terminal with a finger, this causes charge to flow from ground to the terminal, attracted by the charge on the object close to the terminal. This charge neutralizes the charge in the gold leaves, so the leaves come together again. The electroscope now contains a net charge opposite in polarity to that of the charged object. When the electrical contact to earth is broken, e.g. by lifting the finger, the extra charge that has just flowed into the electroscope cannot escape, and the instrument retains a net charge. The charge is held in the top of the electroscope terminal by the attraction of the inducing charge. But when the inducing charge is moved away, the charge is released and spreads throughout the electroscope terminal to the leaves, so the gold leaves move apart again.

The sign of the charge left on the electroscope after grounding is always opposite in sign to the external inducing charge.[5] The two rules of induction are:[5][6]

- If the object is not grounded, the nearby charge will induce equal and opposite charges in the object.

- If any part of the object is momentarily grounded while the inducing charge is near, a charge opposite in polarity to the inducing charge will be attracted from ground into the object, and it will be left with a charge opposite to the inducing charge.

The electrostatic field inside a conductive object is zero

[edit]

A remaining question is how large the induced charges are. The movement of charges is caused by the force exerted on them by the electric field of the external charged object, by Coulomb's law. As the charges in the metal object continue to separate, the resulting positive and negative regions create their own electric field, which opposes the field of the external charge.[3] This process continues until very quickly (within a fraction of a second) an equilibrium is reached in which the induced charges are exactly the right size and shape to cancel the external electric field throughout the interior of the metal object.[3][7] Then the remaining mobile charges (electrons) in the interior of the metal no longer feel a force and the net motion of the charges stops.[3]

Induced charge resides on the surface

[edit]Since the mobile charges (electrons) in the interior of a metal object are free to move in any direction, there can never be a static concentration of charge inside the metal; if there was, it would disperse due to its mutual repulsion.[3] Therefore in induction, the mobile charges move through the metal under the influence of the external charge in such a way that they maintain local electrostatic neutrality; in any interior region the negative charge of the electrons balances the positive charge of the nuclei. The electrons move until they reach the surface of the metal and collect there, where they are constrained from moving by the boundary.[3] The surface is the only location where a net electric charge can exist.[4]: p.754

This establishes the principle that electrostatic charges on conductive objects reside on the surface of the object.[3][7] External electric fields induce surface charges on metal objects that exactly cancel the field within.[3]

The voltage throughout a conductive object is constant

[edit]The electrostatic potential or voltage between two points is defined as the energy (work) required to move a small positive charge through an electric field between the two points, divided by the size of the charge. If there is an electric field directed from point to point then it will exert a force on a charge moving from to . Work will have to be done on the charge by a force to make it move to against the opposing force of the electric field. Thus the electrostatic potential energy of the charge will increase. So the potential at point is higher than at point . The electric field at any point is the gradient (rate of change) of the electrostatic potential :

Since there can be no electric field inside a conductive object to exert force on charges , within a conductive object the gradient of the potential is zero[3]

Another way of saying this is that in electrostatics, electrostatic induction ensures that the potential (voltage) throughout a conductive object is constant.

Induction in dielectric objects

[edit]

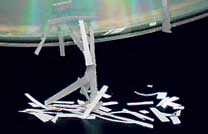

A similar induction effect occurs in nonconductive (dielectric) objects, and is responsible for the attraction of small light nonconductive objects, like balloons, scraps of paper or Styrofoam, to static electric charges[8][9][10] (see picture of cat, above), as well as static cling in clothes.

In nonconductors, the electrons are bound to atoms or molecules and are not free to move about the object as in conductors; however they can move a little within the molecules. If a positive charge is brought near a nonconductive object, the electrons in each molecule are attracted toward it, and move to the side of the molecule facing the charge, while the positive nuclei are repelled and move slightly to the opposite side of the molecule. Since the negative charges are now closer to the external charge than the positive charges, their attraction is greater than the repulsion of the positive charges, resulting in a small net attraction of the molecule toward the charge. This effect is microscopic, but since there are so many molecules, it adds up to enough force to move a light object like Styrofoam.

This change in the distribution of charge in a molecule due to an external electric field is called dielectric polarization,[8] and the polarized molecules are called dipoles. This should not be confused with a polar molecule, which has a positive and negative end due to its structure, even in the absence of external charge. This is the principle of operation of a pith-ball electroscope.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Electrostatic induction". Britannica.com Online. Britannica.com Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Fleming, John Ambrose (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–193, see page 181, second para, three lines from end.

... the Swede, Johann Karl Wilcke (1732–1796), then resident in Germany, who in 1762 published an account of experiments in which....

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Purcell, Edward M.; David J. Morin (2013). Electricity and Magnetism. Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-1107014022.

- ^ a b c d Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jearl (2010). Fundamentals of Physics (9 ed.). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9780470469118.

- ^ a b Cope, Thomas A. Darlington. Physics. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 1465543724.

- ^ Hadley, Harry Edwin (1899). Magnetism & Electricity for Beginners. Macmillan & Company. p. 182.

- ^ a b Saslow, Wayne M. (2002). Electricity, magnetism, and light. US: Academic Press. pp. 159–161. ISBN 0-12-619455-6.

- ^ a b Sherwood, Bruce A.; Ruth W. Chabay (2011). Matter and Interactions (3rd ed.). USA: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 594–596. ISBN 978-0-470-50347-8.

- ^ Paul E. Tippens, Electric Charge and Electric Force, Powerpoint presentation, p.27-28, 2009, S. Polytechnic State Univ. Archived April 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on DocStoc.com website

- ^ Henderson, Tom (2011). "Charge and Charge Interactions". Static Electricity, Lesson 1. The Physics Classroom. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ^ Kaplan MCAT Physics 2010-2011. USA: famous Publishing. 2009. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-4277-9875-6. Archived from the original on 2014-01-31.

External links

[edit] Media related to Electrostatic induction at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Electrostatic induction at Wikimedia Commons- "Charging by electrostatic induction". Regents exam prep center. Oswego City School District. 1999. Archived from the original on 2008-08-28. Retrieved 2008-06-25.